Neural Rendering Small Worlds

2025-11-01

In the previous post we introduced conditional rendering to our implicit neural network, so that it could render different shapes. Some novel double-renders were possible, when we conditioned the network on inputs it had not seen during training.

In this post, we will scale up these experiments to render larger conditioned scenes. From this conditioning, we will then be able to make a large world that we can move around in with our renderer.

RENDERING COLORS

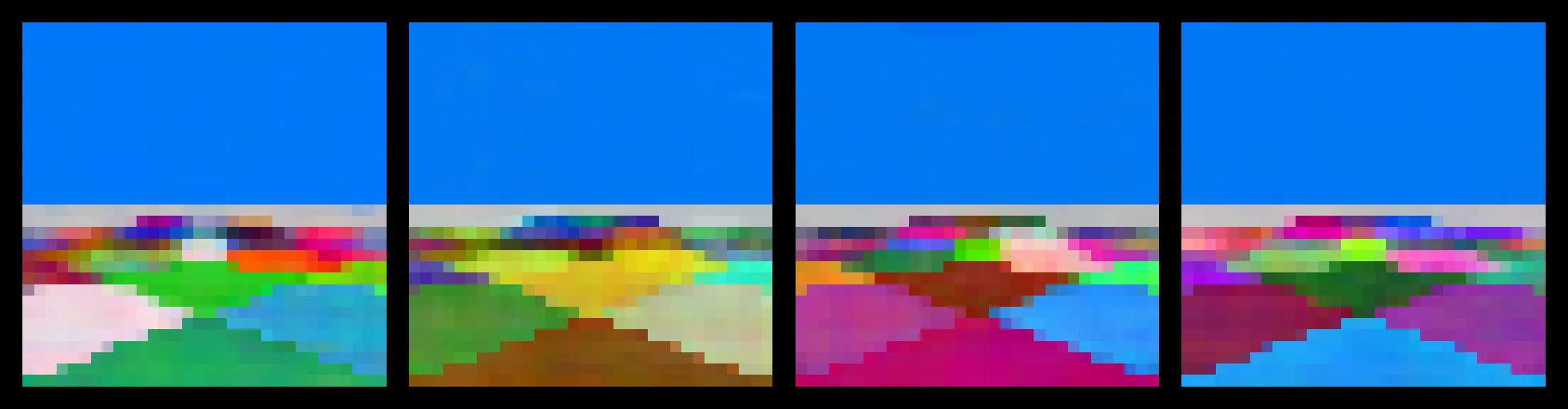

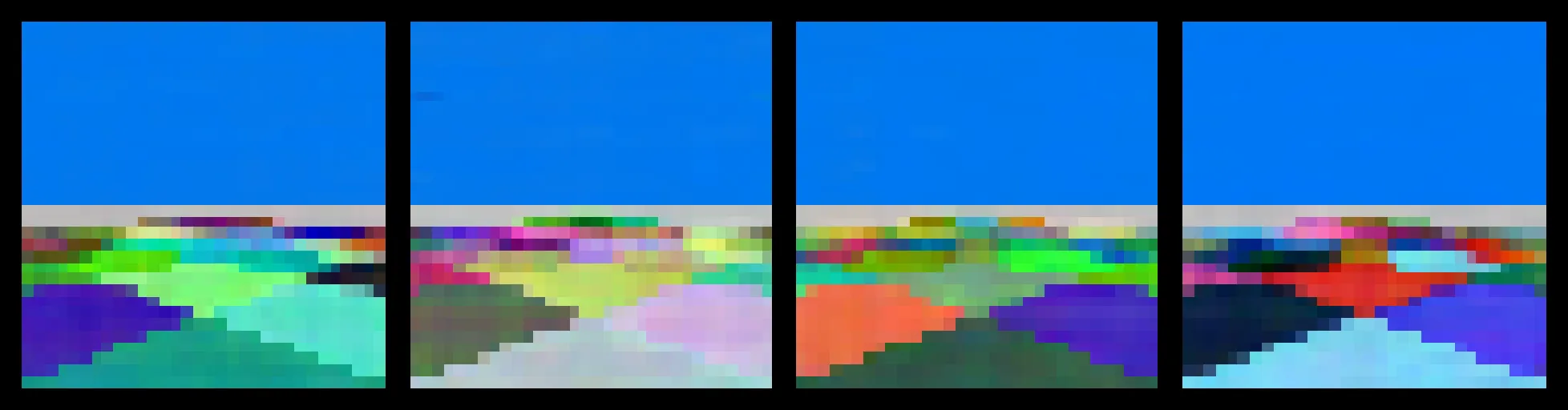

Let's fix our camera to a single pose. Instead of conditioning on the camera, we can condition on a grid of blocks. I'll assign each block a random color, and input these colors as a flat, ordered vector into the network. The results are a controllable grid render:

This proves that it is possible to controllably condition our network at scale. Because the ordering of out cubes is always the same, and the number of cubes does not change, we can make use of a simple architecture. If we were to scale this out to arbitrary cubes, we would probably want something more like a PointNet or a Transformer architecture. Adding camera pose to this now explodes our input space. Instead of the 4-dimensional input from before (with added positional-encodings), we now have a 4 + 64 * 3 = 2,176-dimensional input. It turns out this is fine, as long as we make sure the degree of our positional-encoding is high. In early experiments, I reduced this to a value as low as 6 or even 4. Because the resolution of our rendering is higher (due to the color complexity), this is not enough representational power. Below are the results with a moveable camera and randomly controlling the color change:

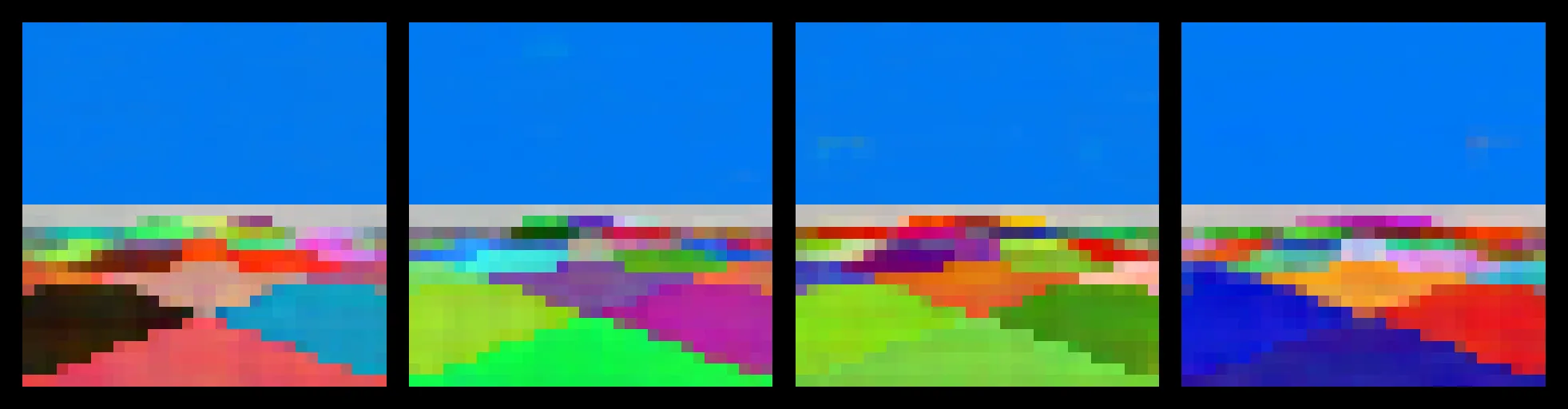

RENDERING FOREVER

This is enough for us to make an 'endless' cube world to walk around in. Instead of training our camera in a boundary of [-4, 4] along two axis, we can just constrain it to the boundary of a single cube's length. Then when the camera passes the boundary of the cube, we move its position to the opposite side of the cube, while simultaneously shifting all the cubes along the axis of movement. This creates an illusion of movement for the player. We then generate a large grid of colored cubes, and remove a region around the player to pass to the neural network. Below is the result:

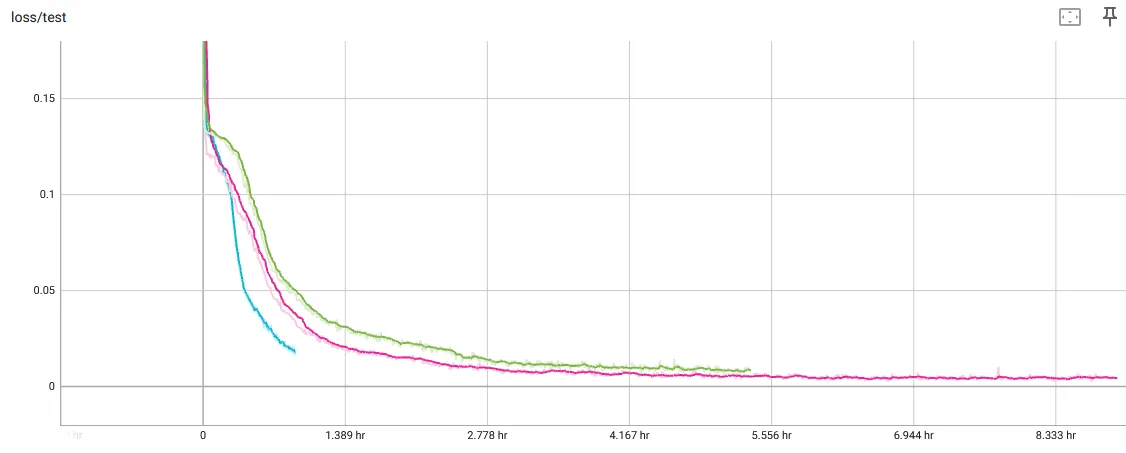

Finally, here are the training curves for some of the experiments:

The blue curve is the static training, which I stopped early because it proved that color-conditioning was working. The pink and green are the 8x8 movement render and a slightly more complex movement render to support data for infinite scrolling. Both trained for about 5 hours on a 3080 Nvidia RTX.

CONCLUSION

As we expand this neural rendering system, the advantages of controlled scalability are clear. By starting from a small problem, we can understand the capacity of implicit neural networking rendering, and slowly expand as the problem requires. In this way, we can keep our model lean. Most of the failures I encountered in the above experiments were due to data. Either the pre-processing of the data was wrong (not enough positional encodings), my camera representation was poorly interpolable (using angles instead of vector direction), or I overengineered my model (early on, I jumped right to a transformer architecture for processing the cube data, rather than trying the simplest approach first).

With this minimal demo, there are many further directions that are exciting to explore. The next step will be to increase the complexity of our world by another dimension.