Tiny SIRENs

2025-10-12

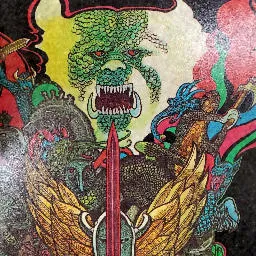

In the previous post I explored using SIRENs to learn scene representations. We made a simple raytraced model of a city and then learned an implicit function conditioned on the position of the camera and the pixel coordinate. This was all on small, 256x256 images. This post briefly outlines two more experiments I tried with SIRENs. The next post, I plan to expand the SIREN experiments beyond the simple ones we have tried, and learn a render of an entire seen, conditioned on the full camera parameters. Before that, though, some small experiments:

SIREN LoRA

Low Rank Adaptation (LoRA) is a technique to adapt large models to low-level domains. By introducing low-rank matrices that additively adapt the linear layers of the model, we can project the larger model to a smaller space. I have been trying to explore ways in which two SIRENs could interpolate a single image. I am unsure if this is possible. Early ideas included training two neural networks, and then blending their weights, with some regularisation to preserve their representations. The other idea was to use a LoRA to tune a pre-trained SIREN on a second image.

As a initial experiment, I took a randomly initialized SIREN and used a LoRA adapter to train it on an image. This worked. Which likely means the neural network is over-parameterized or something.

Compare this training image progression to what a normal SIREN run looks like:

In the later, you can almost see the LoRA models twisting the signals to transform them into the target shape. Now we can train a SIREN on image A, then use a LoRA adapter to retrain it on image B. This works:

If we interpolate the LoRA (by moving alpha from 0 to 32), we do not get the interpolation space we would like:

(and here is the interpolation with the rank halved during adaptation).

What results can we expect? I was aiming for some high-level transition between the two images. Something obviously less clear than the interpolation of a latent space of a larger model trained on various images. Given we are working with sinusoidal signals, it seems that we could also solve this problem simply by shifting the signals – that is, just applying an adative bias to the outputs of the linear layer. This is an unconditioned LoRA, just adjusting the signals at every layer. If we do that, the adaptation is lower quality:

Still, it is interesting to note that the 'signal space' of the SIREN network is complex enough that we can phase-shift the signals to reproduce a second image. After this, I tried a few other LoRA experiments, with smaller models, changing the alpha values of the interpolation layer-by-layer, but the results were not very interesting. It makes much more sense, in hindsight, to stick with data size, and gather more images to create this meaningful interpolation space.

Tiny SIREN

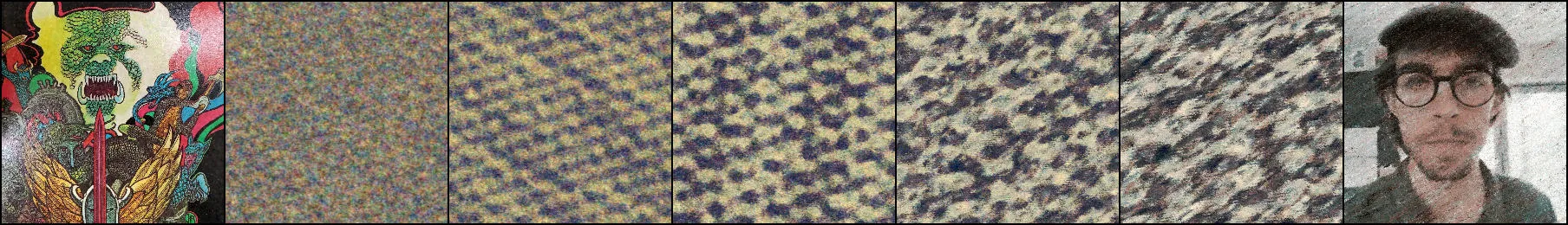

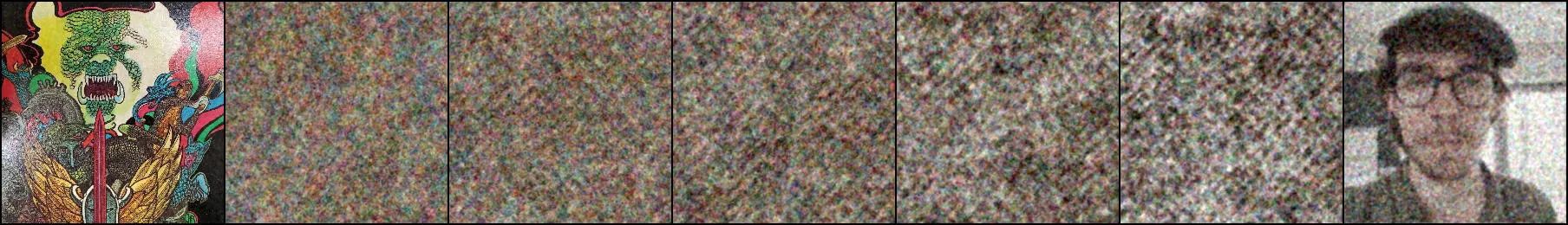

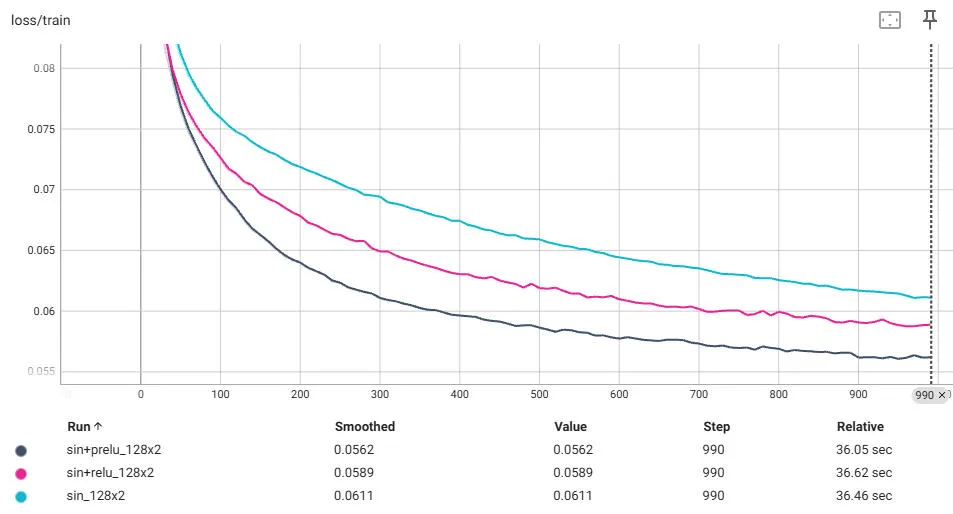

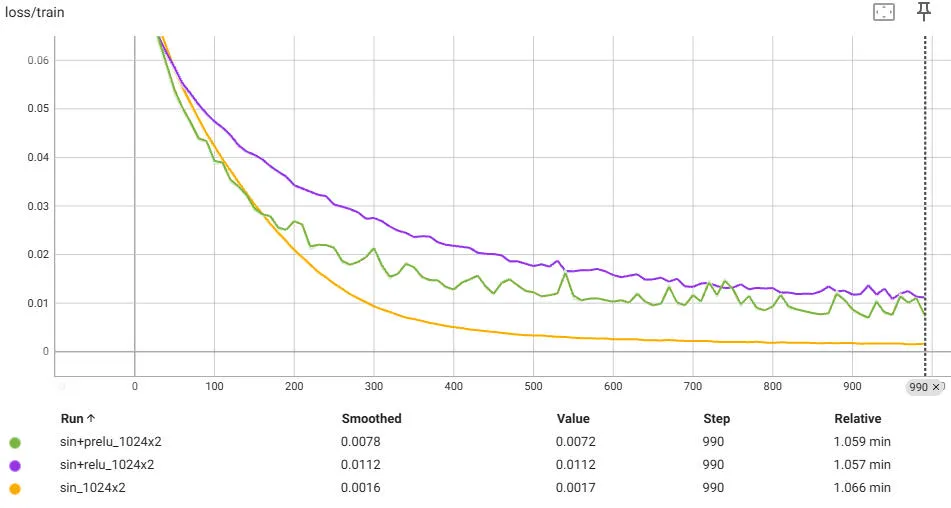

How small can a SIREN network be? Can it be smaller than the image itself? In the original SIREN paper, they used large models for most experiments. 'Large' here is five-layers and a-thousand hidden units. Sticking with two layers, let's train five SIRENs with weights varying from 128→2048. Here are the loss curves:

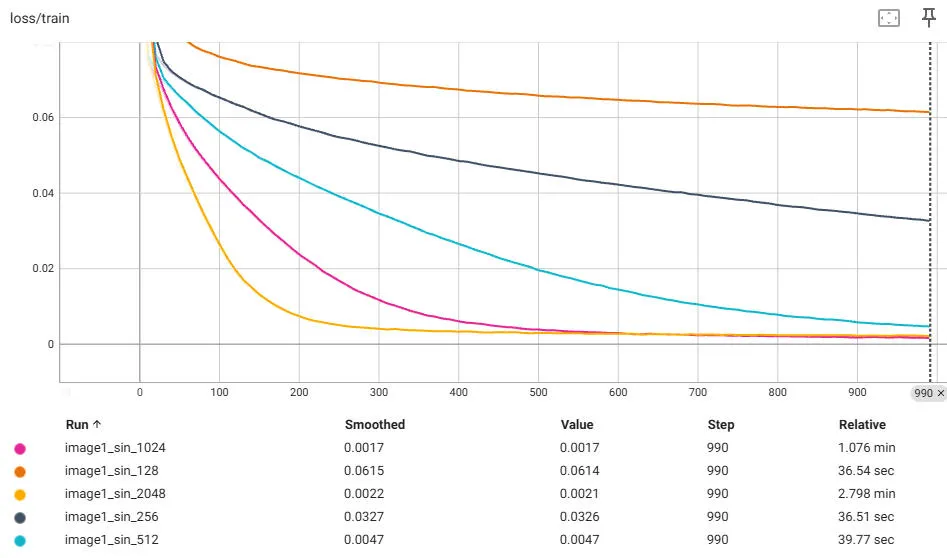

Here are the resulting images:

The original image, encoded as PNG is 171 KB, according to my file explorer. Here are the sizes of the saved PyTorch weights (which is all we need to reproduce the original image):

| Model Size | File Size |

|---|---|

| 128 | 72 kb |

| 256 | 268 kb |

| 512 | 1,043 kb |

| 1024 | 4,129 kb |

| 2048 | 16,445 kb |

The 128-size model, although smaller than our image, is also obviously much worse quality than the original image. Can we push the quality higher? Taking a page from mu-NCA (REF), where they explored various techniques to reduce the size of Neural Cellular Automata networks to generate textures, we can replace the last layer activation with PReLU (which is essentially what they did, but expanded as a set of parameters – there are other additions too, but these aren't relevant). Let's stick with the 256-size model, which is still below the image size. Here are the loss results comparing a Sin, ReLU, and PReLU final hidden layer:

And here are the reproduced image results:

We gain a little bit with the PreLU. It is not really noticeable when we show the image. Also, this does not scale though – in fact, the PReLU becomes very noisy:

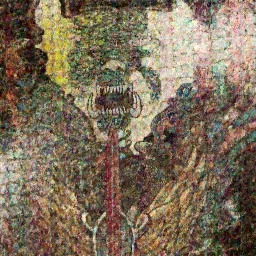

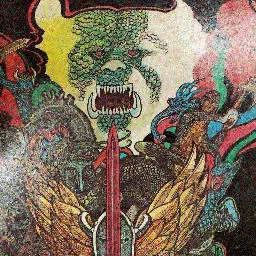

Still, we can reproduce the image with some high-fidelity quality loss with a network that is smaller than the image iteself. What is the smallest SIREN we can make that can reproduce an image to some fidelity? It is an interesting question. The smaller these become, the easier it might be to have a meta-network output them. Then we might be able to scale the learned implicit space experiments that they briefly did in the original SIREN paper. Here is an early result from a 2-layer, 64-unity network outputing a 128x128 screenshot from the Pico-8 game, Poom (scaled up 2x to be visible):

We can see that smaller does not scale in an obvious way. Despite the image being 4x fewer pixels (and Pico-8 only contains 16 valid colors), the reproduction quality is still pretty poor. And, just to show it, the original SIREN network at 2x1024 does really well in reproducing the original:

To conclude: I'm documenting the experiments above so I have them to refer back to. There is nothing too surprising or useful here, but it is was worth exploring these questions to understand more about SIREN models and implicit models in general. The next experiments will go the other way, and explore expanding the data size and the problem complexity. For this, we will need larger models.