Red Cube Neural Network

2025-10-23

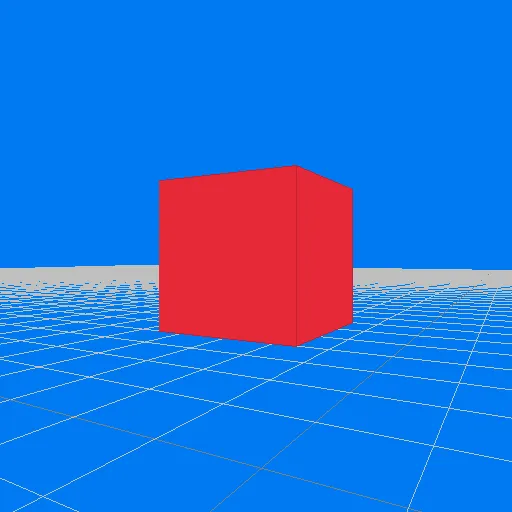

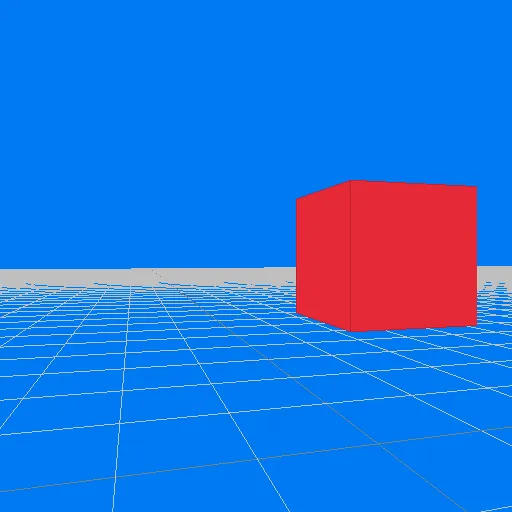

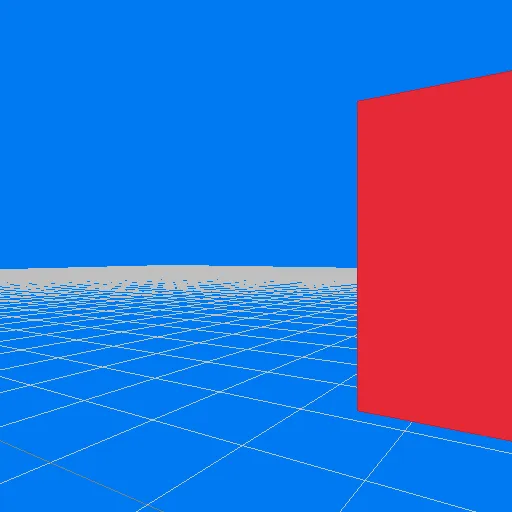

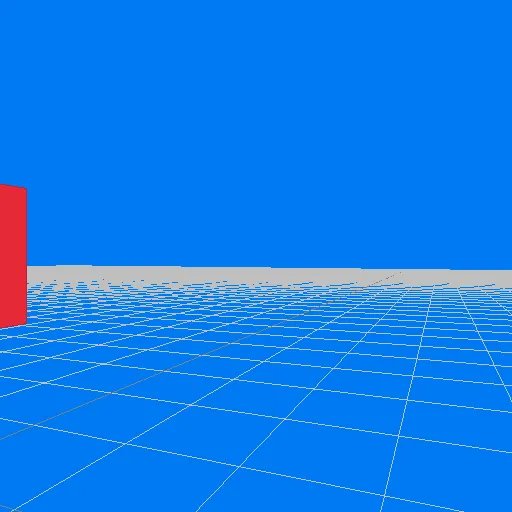

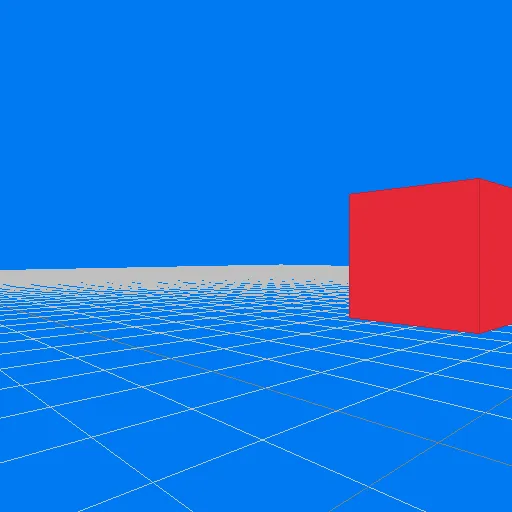

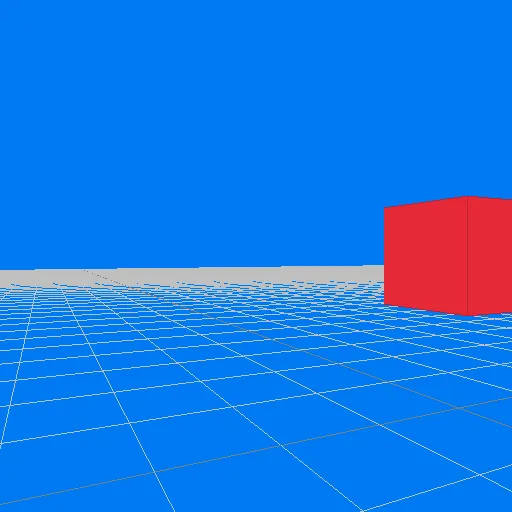

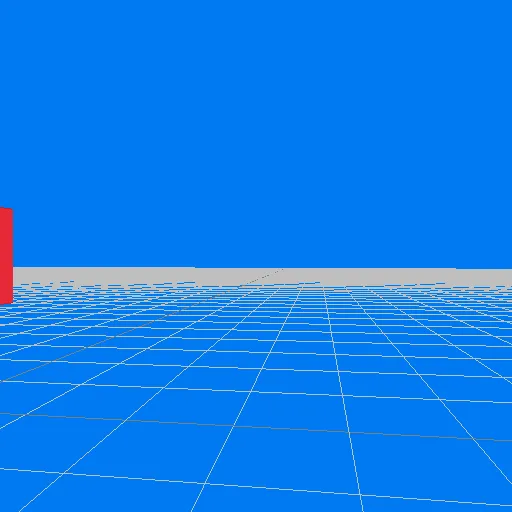

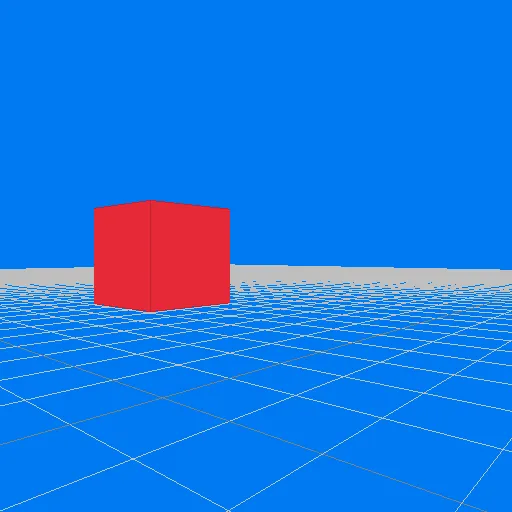

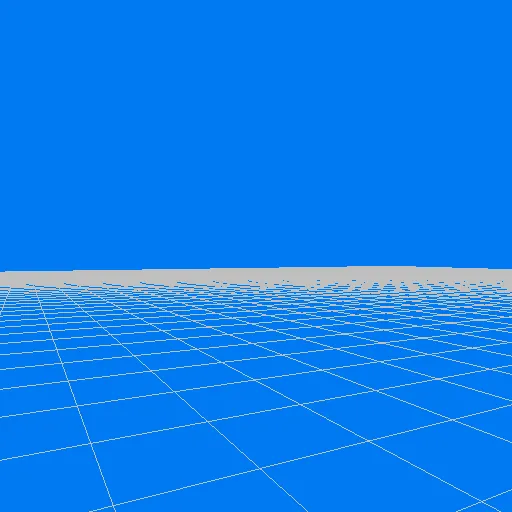

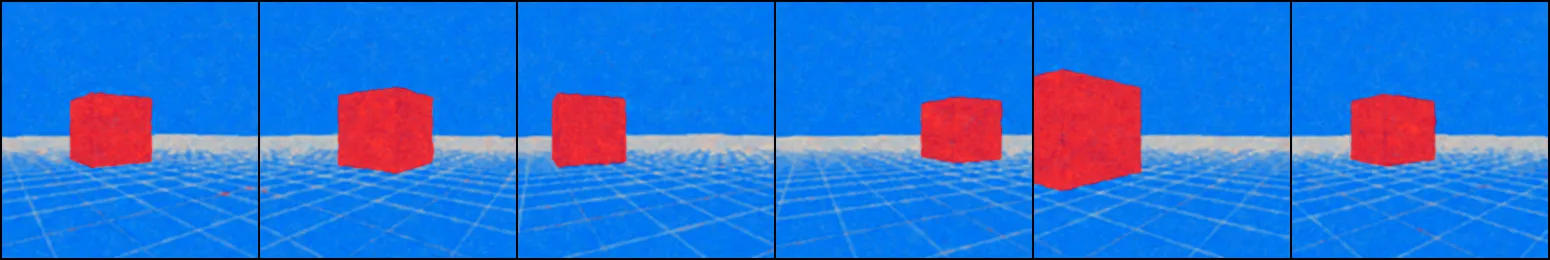

In the previous post on implicit neural networks, we explored small SIREN models. We saw how small we could make a SIREN network so that it could render a picture. We experimented with combining LoRAs and SIRENs, with not much success. In the post before that we rendered a small city, conditioned on the position of the camera using a neural network. In this post, we will extend these experiemnts. Instead of a city, we will simplify the scene: a 1x1 red cube above a 3D 4x4 grid plane on a bright blue skybox. Here are some renders of this scene, with the camera posed randomly within the grid bounds:

This scene is rendered through classical rasterization algorithms. SIRENs and NeRFIEs render scenes with data, instead. But for them to be able to fully capture these scenes, a lot of data is needed. A lot. We can do a quick calculation of the size of our space: if we subsampled a small patch of [0, 1] ground along two axes in substeps of 1,000 that is 1,000,000 samples. If we introduce a camera that rotates along the vertical axis at a low resolution of, say, 360 degrees, a rotation per degree, we now have a sample space of 360,000,000 possible states. This does not take into account the pixel density, which if it is a 32x32-pixel image would make the sum total be: 368,640,000,000 possible states. If we take a relatively large SIREN model with a few layers, sample this space randomly to gather 100k datapoints, and then test this model on a new position in the scene, this is the result:

Now, SIREN models have their problems. But we are also sampling less than a tenth of a percent of the possibility space of our scene. Neural networks are fuzzy look-up table generators, with some minor interploation capabilities that we call 'generalization.' To expect the neural network samples between our datapoints to have any coherence in low-data regimes is a mistake. We are requesting of our model an understanding of spatial handling, object consistency, movement, perspective, all with very little data. It seems easy for us, but we have accrued enormous amounts of spatial understanding over our lives.

This is why foundation models require so much data. Across all the domains they are being trained on, there are some common patterns they are being exposed to continously; this allows it to learn these patterns. But a model must be exposed to millions and millions of examples to get have the generality we see in the largest models.

Another problem is that neural networks are pretty poor at learning samples until they see them multiple times. If we just had to show our neural network a sample once, and could move on, it would be much easier to amass knowledge and generalization. But even for a problem as simple as rendering a red cube, the number of data points is extraordinary.

First Red Cube

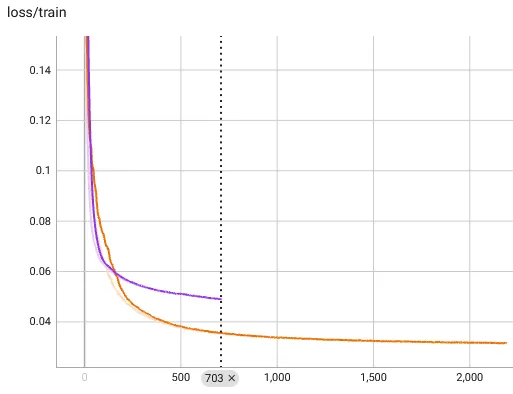

Let's stick with 100k samples of the scene, for now. Instead of a SIREN model, we will use a NeRFIE-like model. The difference is that instead of the high-frequency signals being handled by the model parameters, we will input higher-frequency information into the data by computing positional encodings of our low-frequency position and orientation. Instead of a six-dimensional input (x-position, y-position, x-direction, y-direction, x-pixel-position, y-pixel-position), we will have a 126-dimensional input (an additional 20 positional embeddings for each of the features). Our network will be a simple 5-layer ReLU. Here are some results on the training data:

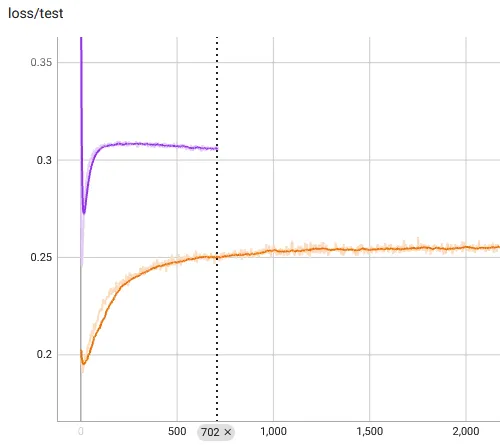

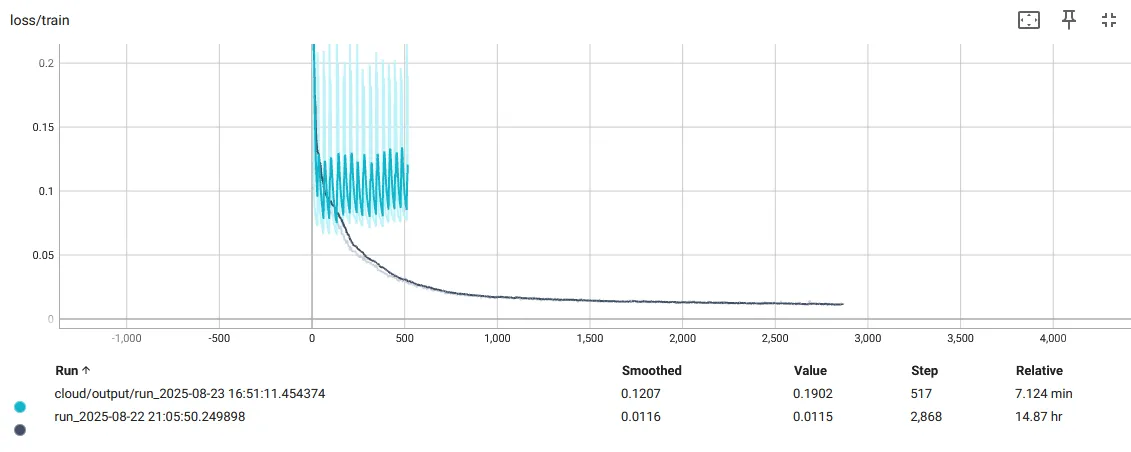

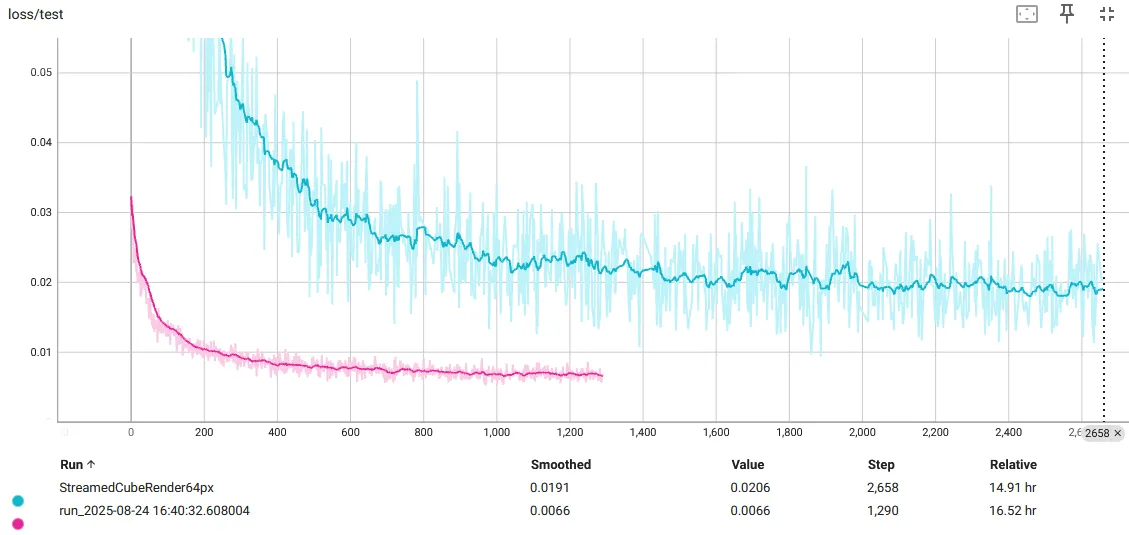

What we haven't done in previous experiments, though, is look at the test loss. This tells us how well the cube is rendered from unseen poses. A plot shows us what is wrong. I have added the SIREN results to this, too, to show you how badly both models overfit the training data, despite our good training performance:

We might be producing good training renders, but our results are terrible otherwise. This is not a model problem. It is a clear data problem. We did not experience this problem with the city render because the input space was a lower-dimensional, only being 2D position data. We need more samples for camera rotations to work.

To simplify the problem, we will focus on a 32x32-resolution render of the cube scene. This will allow us to avoid memory requirements from large datasets and large models, and instead focus on solving the minimum problem. Later on we will scale this up in a fun way.

More Renders

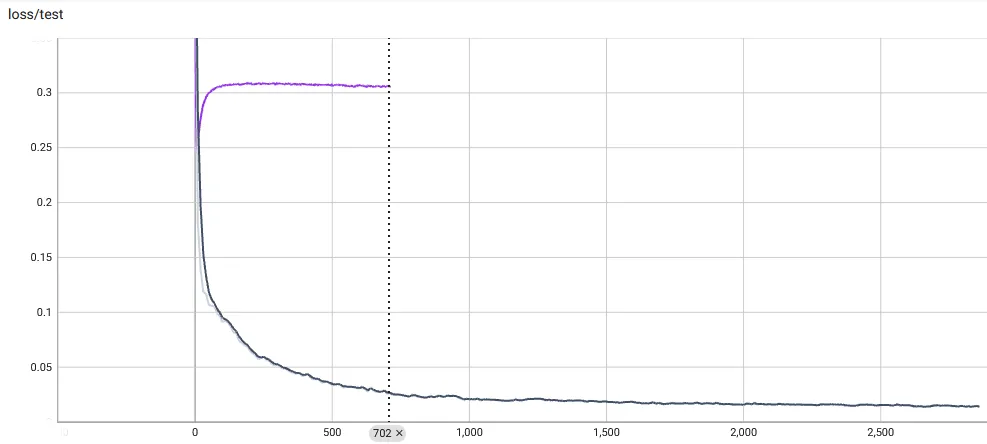

The cost of more samples is more memory. Managing this memory is one of the slowest parts of training a neural network. How to deal with large datastreams is the hardest problem most of these learning pipelines have to solve. The faster your memory handling, the faster your training. Because of memory requirements, we can stream the data to the GPU when we need it to train. I find this approach clunky, though. Especially when the data collection process is slow. In domains where there is finitely collected data, it makes sense to solve it this way. Instead, for the problem of rendering a cube, we have access to as much data as we like. The render step is also quite cheap when done in parallel with the training.

I set up a process that continuously filled a group of data buffers when any one was empty. A second process pulled from these buffers and iteratively trained on it, until a new buffer was available. If the buffers updated too slowly, the network would overfit to the buffers and oscillate:

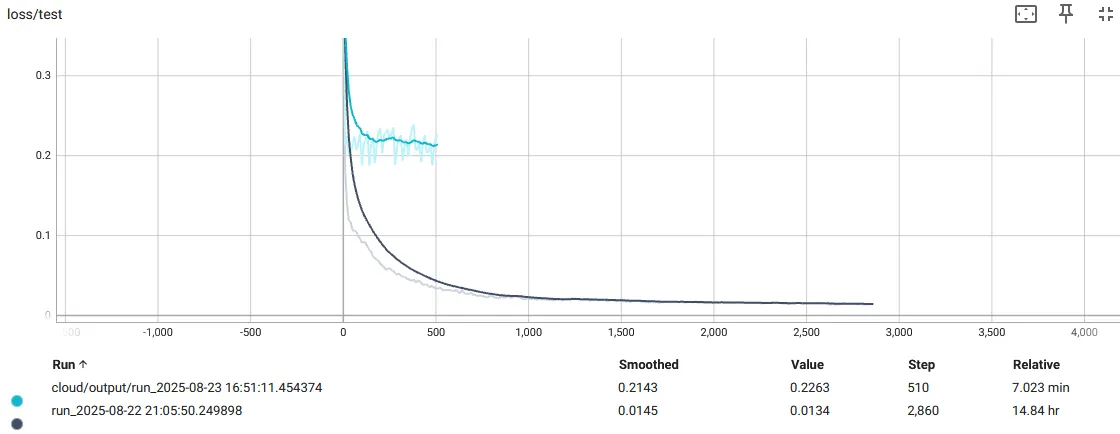

If the buffers are small enough and replenish fast enough (every epoch), the training is very smooth. At the start of training, we hold out a small dataset of test images. We now get nice, smooth train/test loss curves. I have added the original, overfit model to the plot as comparison. Recall, this is the test loss, which is how well the model renders from an unseen pose:

And the resulting 32x32-pixel red cube render is very clean:

There are now opportunities to reduce the training time, with architectural decisions -- maybe some skip connections, better learning scheduling, etc., but the hardest problem has been solved: understanding the minimum model and the scale of data required to fit the implicit function and generalize well to unseen poses.

More More Renders

Let's render a 64x64 image now. We could try larger images, like 256x256 even -- and also explore the power of our implicit representation to give us variable image resolutions for free. But instead, I'd like to do things on the cheap: the current pipeline would need some work to handle the larger memory managment. Rather, let's take some 512x512 renders and compress them. We will use a TinyVAE, to generate 64x64x4 latent representations of our images. The additional step in our pipeline will then be to render 512x512 images and pass these through the TinyVAE's encoder before training on them. Then, at inference time, we can take the TinyVAE decoder and upscale the images we output, to have a 512x512 render.

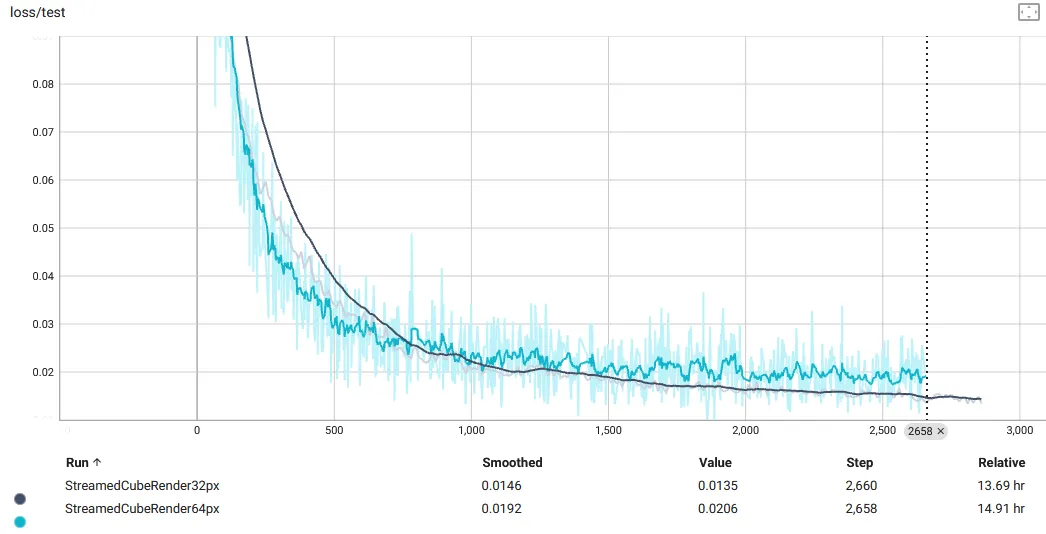

First, the results of our implicity model when fitting 64x64-resolution images instead. The training time was about the same, as seen in the comparison plot below. The test loss for the 64px model is more noisy because I decided to change my test-sampling procedure to sub-sample the test data to reduce evaluation time during training. I made no changes to the hyperparameters -- this makes sense in the implicit-rendering world, where the domain representation for your network is unchanged as the image scales.

And here is the network now trained to predict the TinyVAE latents. Below is also a plot comparing the test loss curves to the 64px model. I am unsure why the test loss is better behaved -- perhaps the latent space representation is easier to learn to due the way it is compressed to introduce image redundancy? I am only visualizing the first 3 channels of the 4-channel latent embedding:

And finally, a video of the decoded latents in their dreamlike washiness. Training time for this was about 10 hrs on a RTX 3090. A longer training time would reduce some of the bluriness, of course:

We don't really need to the upscaling power of the VAE to solve large-image generation with implicit neural image rendering. This pipeline is interesting because it opens up other possiblilites for downstream models. I am not really sure what they are yet. What if the VAE provided some stylistic changes to the image? What if the VAE latent space was unstructured? It could be expensive to gather enough real-world samples to build a viable render of a scene -- instead, some VAE could help here. Or: it is more computationally efficient than one model generating the entire high-resolution image end-to-end?

Next Steps

A red cube is compelling. A kind of 'Hello World' of neural implict renders. I especially like the details, such as the depiction of the wire-mesh render when the camera enters the cube volume. With this foundation we can do some interesting things now. Here are some further ideas I would like to explore:

- Render multiple shapes, and condition the network on the shape representation.

- Include in the network inputs the position of the cube, then move the cube as well as the camera.

- Render multiple entities, even varying numbers of entities.

- Explore ways to exploit the implicit nature of the rendering to change the render, as well as finding ways to make the positional representation of the camera unbounded.

- Return to the LoRA experiments, this time using the cube render to transfer to a new shape.

And of course: where is the game in this? We get far more control out of this approach than world model-based methods. Scene consistency and dynamics in world models will make good progress over the next year, but I find myself preferring this approach, as it is far more controllable from a data-driven side, allowing you to finely tune the spatial understanding and representational power of the model. It also nicely separates view and model, similar to many game software architectures.